Centre for Neuro Skills

In 1977, Ed Breen of the Home Insurance Company identified a problem within the healthcare provisions for workers injured on the job. He approached a group of academics with a win-win solution, if it could be accomplished.

A number of individuals acquired catastrophic brain injuries in the scope of their employment with Mr. Breen’s company. Despite months of treatment in hospitals, these people were often left with tremendous levels of disability. Such disability translated to a very poor quality of life for the injured persons and their families, and a very high cost of continued care over the injured persons’ lifetimes.

Mr. Breen’s solution:

Reduce their levels of disability to an extent greater than that achieved at the hospitals, which leads to:

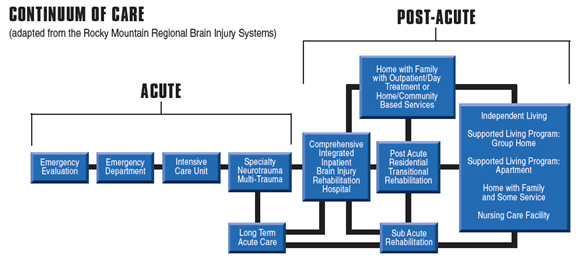

So, advances were made over the last 40 years in treatment of people who have sustained brain injuries through work-related incidents. Worker’s compensation professionals specifically designed an entire continuum of treatment to manage the catastrophic claims of their parent companies in concert with health professionals. Treatment was extended to rehabilitation in post-acute care; results spoke for themselves with many more people returning to higher levels of productivity and overall health, thus reducing long-term health costs.

Worker’s compensation has improved brain-injured persons’ level of care from what it was in 1977. I ask now, is that enough?

In California, the guidelines that are used by carriers and utilization reviews organizations are simple. They are presented from the Medical Treatment Utilization Schedule (MTUS) below in their entirety:

“Patient rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury is divided into two periods: acute and subacute. In the beginning of rehabilitation therapist evaluates patient’s functional status, later he uses methods and means of treatment, and evaluates effectiveness of rehabilitation. Early ambulation is very important for patients with coma. Therapy consists of prevention of complications, improvement of muscle force, and range of motions, balance, movement coordination, endurance and cognitive functions. Early rehabilitation is necessary for traumatic brain injury patients and use of therapy methods can help to regain lost functions and to come back to the society. (Colorado, 2005) (Brown, 2005) (Franckeviciute, 2005) (Driver, 2004) (Shiel, 2001)”

The above definition does not reference the continuum of treatment that has been used consistently over the last four decades. The continuum is shown below:

It is said that if “one has treated one person with a brain injury, they have treated one person with a brain injury.” That is to say, no two people who sustain a brain injury are alike. Brain injury is one of the most, if not the most, complicated medical conditions to be encountered. And, brain injury is often accompanied by other system injury or involvement.

Not only is brain injury tremendously complex, but so must be treatment for brain injury. The above continuum provides for numerous treatment setting options, each with distinct dosing advantages for specific subgroups of patients who are experiencing unique constellations of deficits following brain injury. These deficits can include medical, physical, communicative, cognitive, psychological, and/or behavioral disorders requiring careful selection of the treatment setting most likely to properly dose treatment of the problems presented by any given individual.

So, why does the State of California operate under such simplistic guidelines? Is this the best we can do?

One solution may be to adopt other guidelines that have far better information to offer pertaining to brain injury. Two of these include the Colorado Medical Treatment Guidelines (2012) and the Official Disability Guidelines.

Brain injury can predispose the brain to neurodegenerative processes and may be implicated in a host of diseases such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), Parkinson’s disease multiple scelerosis, amyotrophic lateral scelerosis, stroke, epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease and others. The simplified explanations in this post allow us to consider whether we are monitoring and treating neuroinflammatory influences chronically and properly after brain injury.

Information

Associated Considerations

So, we must consider whether an approach that addresses behaviorally accessible avenues such as diet, sleep, and exercise combined synergistically with endocrine, immune dietary and exercise interventions to quiet inflammatory processes in a previously injured brain has utility in accelerating recovery, furthering recovery, providing neuroprotection for residual, as of yet, uninjured cells, and/or preventing neurodegenerative processes to be accelerated over those of normal aging.